Conducting Research— With a goal in mind.

Solving complex problems is the main reason organizations hire me. You might think the reason to hire me is because I design and code, but these are tools I use to create solutions. My work is dedicated to finding solutions to problems, not the creation of artifacts. To get to solutions you need to understand the problem. That’s the complex part. Solutions are the tail end of the process. Learning more about problems is the beginning of wisdom, and it’s this wisdom I bring to product teams.

But investigating problems is hard work. Doing this has its own challenges. It is not an activity that can be done once and forgotten. Research is a strategic activity. Research for the sake of research isn’t helpful. You need a goal in mind.

Where do research goals come from?

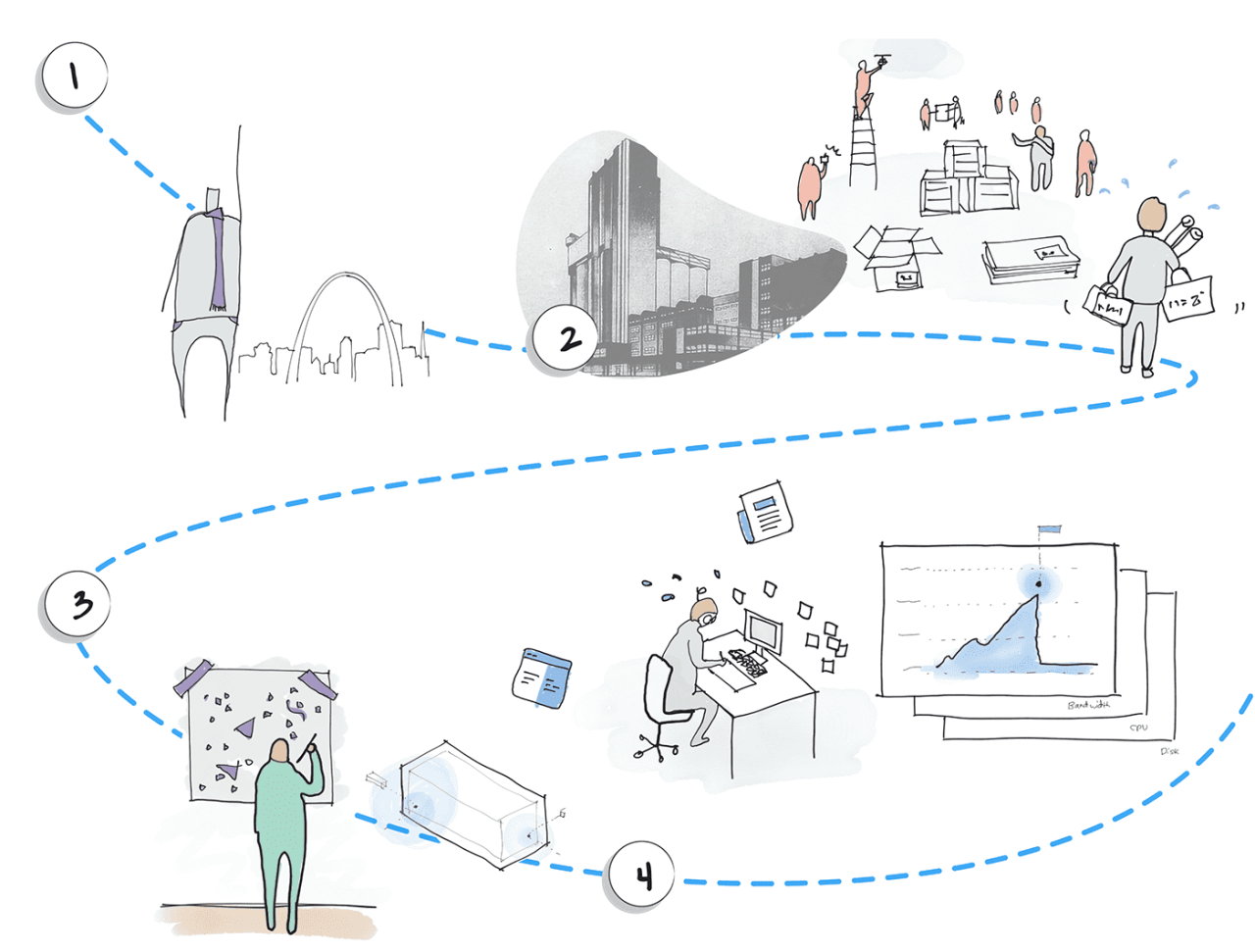

When professionals attempt to solve things, the first step is usually some form of research. Whether informal or formal, the process of gathering facts and observations is a crucial first step. Doctors observe their patients, mechanics inspect vehicles, architects review building sites, and designers learn about the problem at hand.

So what’s so hard?

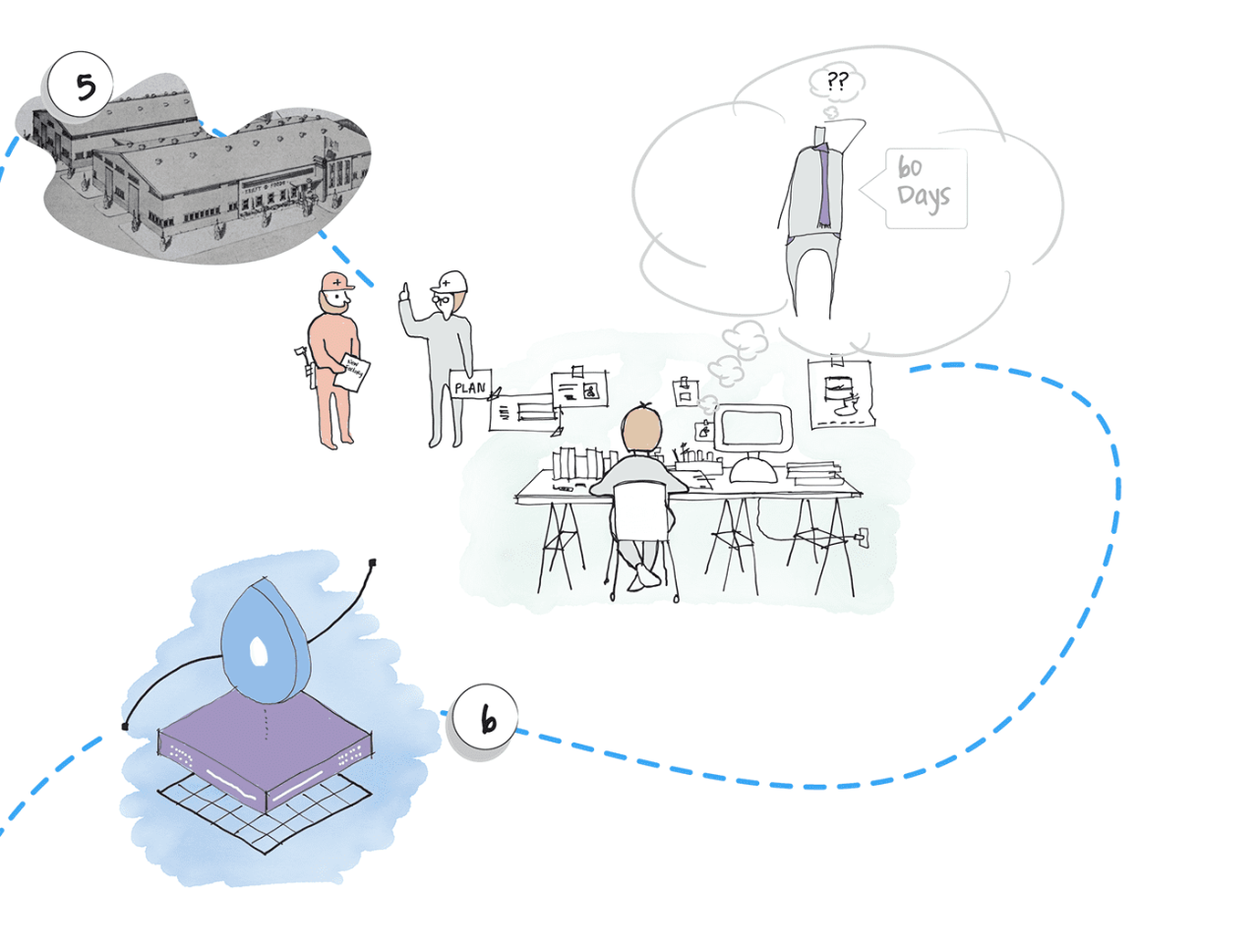

The challenge comes from understanding the goals of those we’re trying to help. A patient may be seeking short term pain relief over long-term health. A car owner might need a quick tune up, not a full repair. An architect's client might have different priorities, that conflict with the building site.

The shared goals of those people we serve focuses what our research goals will be. Misalignment in this area is all too common. Being aware of assumptions and identifying gaps in what we know, is critical to doing research right. Often, we don't even realize if the problems we're researching are truly important to those we aim to help.

The same is true in my work as UX professional.

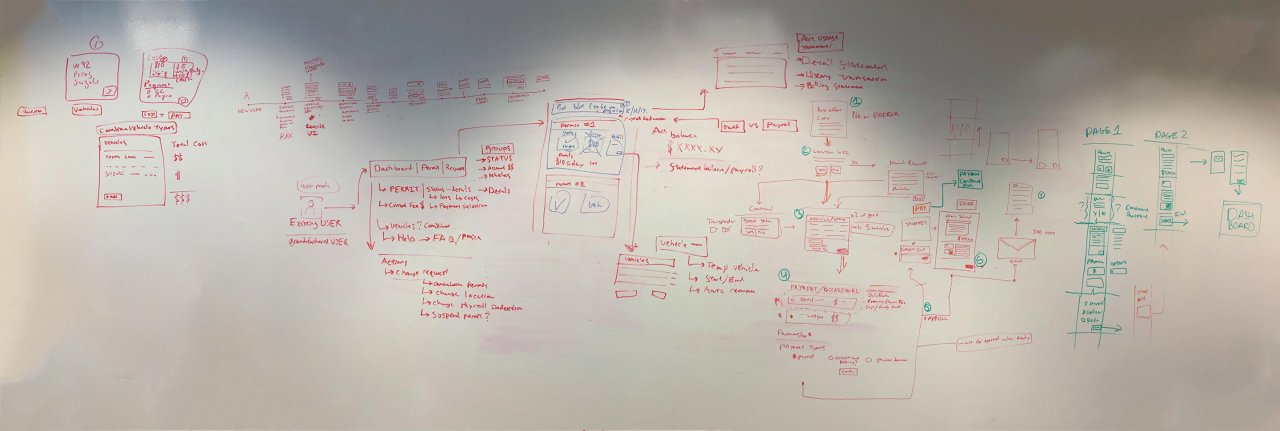

When addressing complex user experience problems that impact entire industries, the problems are often poorly defined or lack consensus. Worse, there’s often no agreement on what the problem is. Before you even pick up the notebook to talk to people, it's super important to get on the same page with your team about what you're trying to achieve with your research. In my experience this is the first step that has to happen.

It’s not what you think the problem is.

In recent years, the UX research side of my profession has faced growing skepticism, sparking debates about its value and necessity. Two camps emerged, one that dismissed UX as just another nice to have, and others advocating for extensive research. Many companies opted to gut UX research resources, with the hiring sprees of yesteryear suddenly disappearing. Less and less openings for dedicated research professionals appeared.

The push back against highly trained research teams, especially in enterprise and SaaS settings, has a lot to do with a perceived lack of results. Some of the harshest critics of research came from companies that hired 100’s of design professionals and product professionals only to find that their spend was outweighing return on investment.

Research often got the short end of the stick. To be honest, however, in my experience, many UX designers often lack the expertise to conduct proper evidence-based studies. (I used to be one of them). It humbles oneself quickly to have my research approaches, poked and prodded by UX research experts.

But unexpectedly and often, I’ve come to see a general resistance in designers, product managers, engineering, and even leadership against running research the right way.

The consequences of doing it wrong are enormous.

To bring UX research to a skeptical organization, reframing the work as strategic vs tactical can be very helpful. Strategic UX research can overcome the skepticism found more frequently in companies burned before by running one off research initiatives. By aligning all the key players– including the decision-makers to the end customers,— on the shared goals from the outset.

Strategic research requires understanding not only the needs of the users, but also your organization objectives. Gut checking with your stakeholders about what goals are, and what of these goals can be measurable and achievable. Doing this, I personally have experienced the work I did became more valuable and relevant to the organizations I worked for.

By shifting the perception of research from a one-off activity to a continuous process of discovery, you can help reduce “feature anxiety”. You work with stakeholders in workshops, design sessions, and even early-stage interviews. By bringing stakeholders to the users, you create a shared understanding of the problem space and build consensus around potential solutions. This "research before the research" approach helps to establish a collaborative environment where everyone feels invested in the outcomes.

To see around you takes constant effort.

Research isn't a one-off phase in a project; it’s a continuous search for opportunities that supports the entire journey. When done right, research remains invaluable throughout the product's lifecycle, supporting a data-drive culture within your organization. It can help ground the culture of a product team or even a company. Designers and researchers serve as stewards of knowledge, leaving a trail of insights to guide future problem solvers.

But what happens after everyone agrees to the needs, problems, and goals?

Well depending on the situation, I find that the next logical step is find the people who are either;

a.) Directly impacted by the problem you're aiming to address.

b.) Current users of the product or service you're enhancing.

c.) Individuals who are currently addressing the problem, including those using different methods or approaches than you propose.

Each situation requires a tailored approach, but a common starting point is to revisit your prior work. Identify assumptions that need to be challenged. What assumptions need to be challenged? You can start with a broad audience but let your research goals guide in your search for people to interview. Start with group interviews if you’re struggling to narrow it down, but gradually get more precise with your user group to achieve a diverse and relevant participant pool. Utilize surveys, market analysis, and existing research to inform these crucial research-shaping decisions. Just talk to people first.

But don’t stop here, this isn’t sufficient evidence. You now only know where to look. With a large enough audience pooled, you can further segment people by specific attributes. Basic demographic information can be a helpful starting point, but it's often superficial. To address real-world problems, you need to understand people's motivations. Explore why people behave the way they do.

Usually this would be a phase you might opt to create a persona of your typical users. Something to communicate what a possible user could be. Many in the profession agree that this isn’t helpful anymore. In fact it obscures who your users are. We solve problem for individuals. People with real names and lives. That means accountability. If you want your team to help make someone’s day better when they use your product or service, best know who they are after you talk with them. A persona won’t get mad at failing usability because personas are not real people.

When you do get around to interviewing people, I recommend involving a mix of product team members and developers in these early stages. This brings along the entire team and really drives home what your users and customers need. And at this stage, since our goal is to shape our understanding, relying on initial assumptions and exploratory research is perfectly acceptable.

But here is where loose feelings need to meet concrete reality.

Good design requires research, but action too.

If you’ve done everything right, we can begin testing our understanding with real users. Resist the urge to create design for design sake to use with interviews; focus on open-ended conversations.

When thinking about User interviews, think of them really as simple interviews. Avoid the school of journalism here, and reach for psychology. Look for those users that are suffering the most with the current user experience. Listen intently, build rapport, and ask follow-up questions. Let the user speak more.

It might be shaky during the first few interviews, but the feedback from the most vocal users will help you refine your interview questions. Take good notes and categorize findings into problems and potential angles to solve them. Identify what's working and what's not.

Pay attention to what isn’t said. Are people missing a helpful tool? Are users missing a helpful tool? Are key assumptions not even mentioned? These observations can be just as valuable as direct feedback.

This targeted approach effectively narrows down the research landscape into actionable work. You should now have evidence to gut check (or not) any assumptions undertaken and set alignment between business goals, design goals, and user needs. You uncover any misalignment, doublecheck the problems you're trying to solve.

This key step is often overlooked. I learned early on that pausing and reevaluating can save entire projects, especially when research is planned without clear criteria for reevaluation. Before scheduling time-consuming ethnographic or longitudinal studies, regularly review and validate your research assumptions. It's better to solve the right problem, right, than to meet arbitrary research timelines.

Research hype curve, and the danger with ignoring it.

When your research direction seems to be hitting its mark, take the time to examine sample size and check if it’s representative. If done right, your interviews with a diverse group will yield accurate data.

As you continue talking to users, ask thought-provoking, open-ended questions informed by your previous interviews, and listen with an open mind. Remember that people are experts in their own problems, but usually are not empowered to develop effective solutions. As a designer, our role is to leverage their insights, and design effective solutions from it. If users ask for a feature, ask why would find this feature useful.

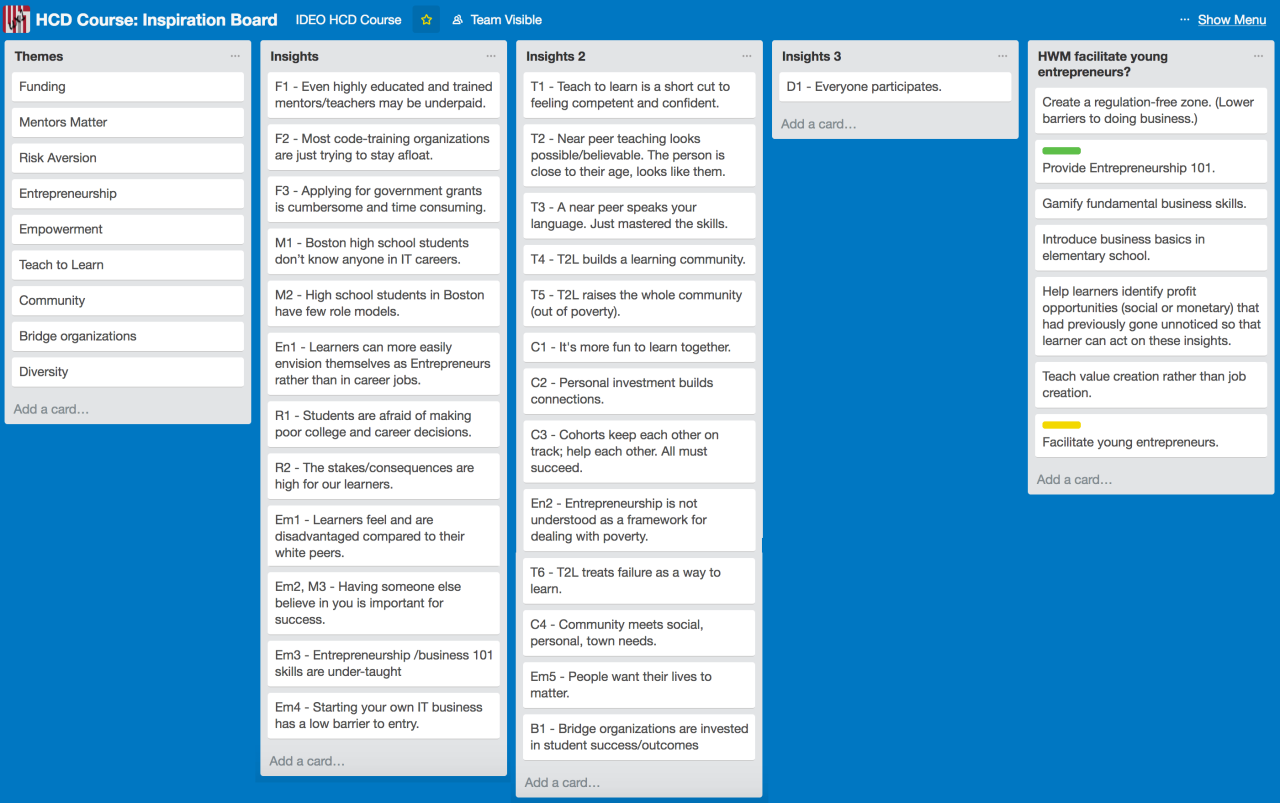

After much interviewing, you’ll be swimming around in sticky notes and text files. Don’t fret— it’s all part of the madness. Summarize each interview as soon possible and look for repeated patterns and themes. Visualize these findings to facilitate communication and analysis. This analysis will help your team prioritize tasks and create a backlog of work.

Research is a team sport. Involving team members from various areas in the research process helps ensure that insights are heard by all and inform decision-making across the organization you work for. I often refer to "Build Better Products" by Laura Klein & Kate Rutter for guidance on conducting effective interviews and research. A key point from their work is that research not shared loses its value quick.

The hype curve for research can be short lived. It can be exciting at first, the entire team can be eager to brainstorm solutions, but it's best to encourage them to wait until sufficient evidence is gathered. After analyzing the data and identifying patterns pointing to potential solutions, the product team can then explore their viability. Regularly updating the team with research playbacks, informal reports, and contributions to a centralized research repository ensures that, even as the initial enthusiasm fades, insights remain accessible, diverse perspectives are considered, and valuable knowledge is preserved for ongoing decision-making.

When the excitement fades, keep the research findings readily available. Senior stakeholders may need reminders of crucial insights. Be prepared to defend your recommendations with the evidence you've gathered.

Some examples my research work.

Case Study: Boston History Database Prototype

Designing a People's History of the New Boston: a fun pro-bono project to help some of my colleagues at MIT.

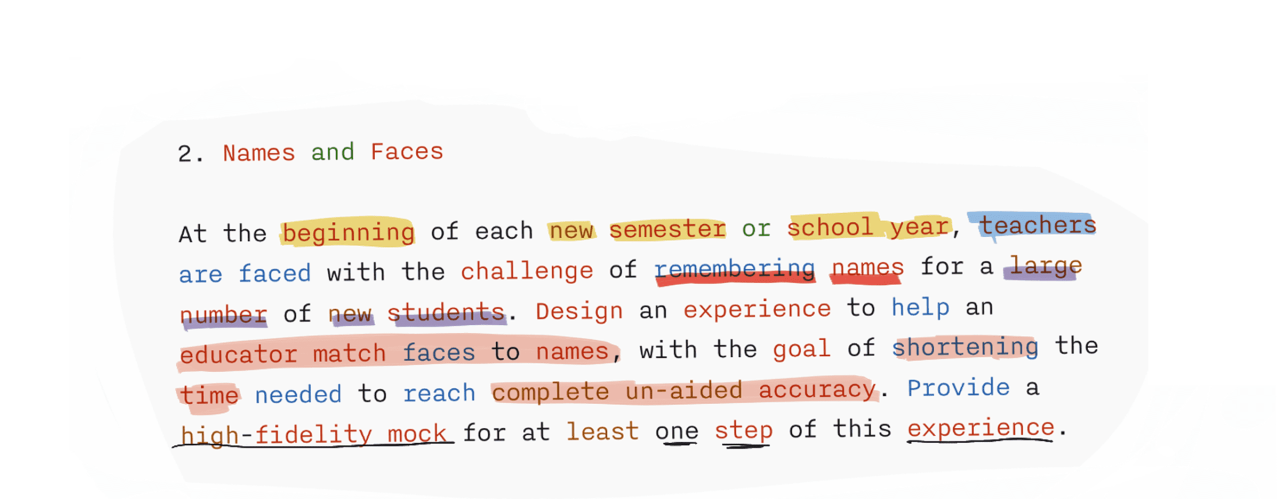

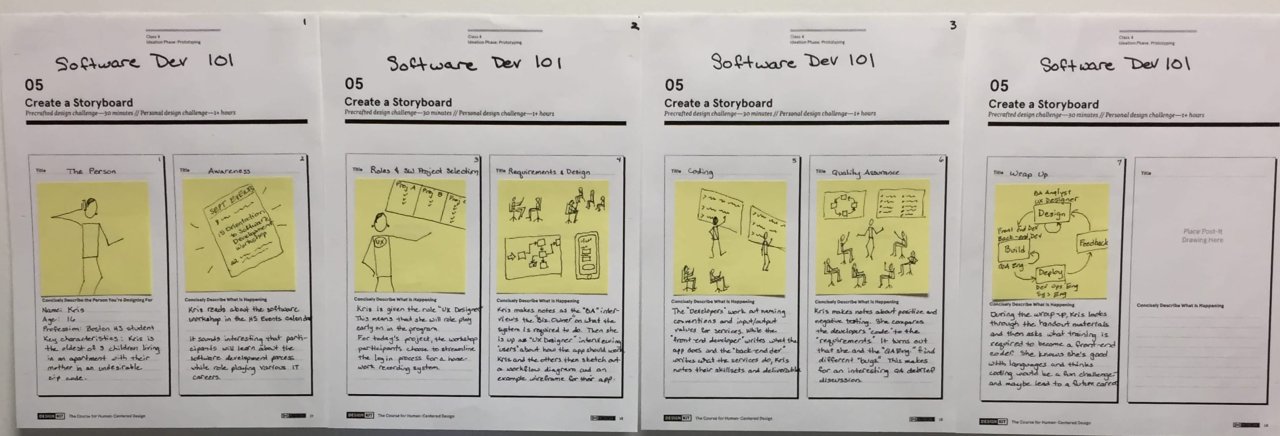

Case Study: Big Tech UX Interview Question

An example of a helpful tool for learning and remembering names and faces.

Case Study: Foundation Medicine UX and UI Work

Cutting Edge science meets modern UI. Contract work with Foundation Medicine was focusing on designing around existing EHR and Healthcare research and ...

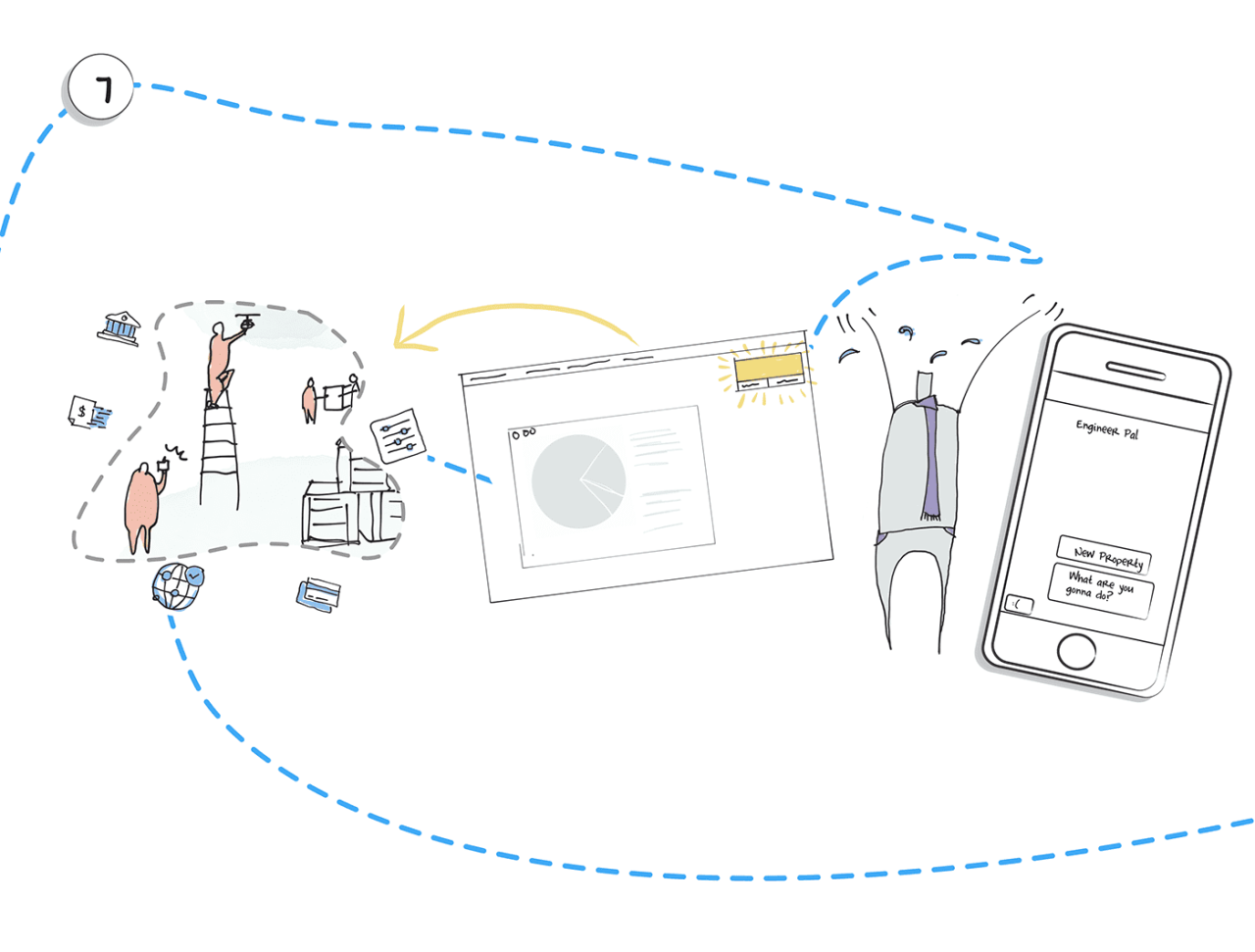

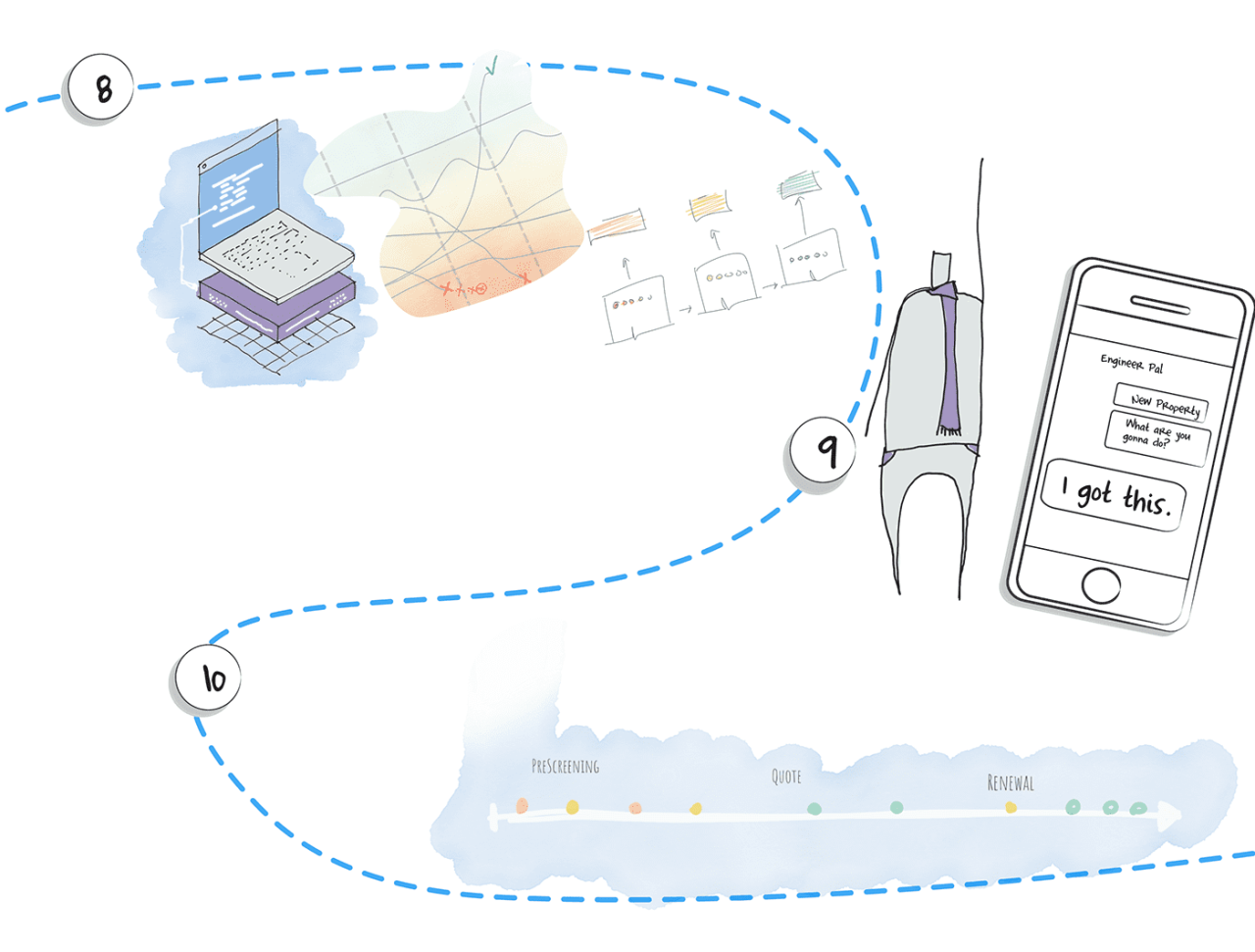

Case Study: FM Global Rapid Prototypes

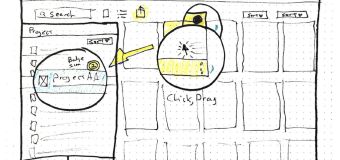

Researching problems, designing solutions, building prototypes. Showcasing how design can be leveraged to bridge the gap between design and tech.

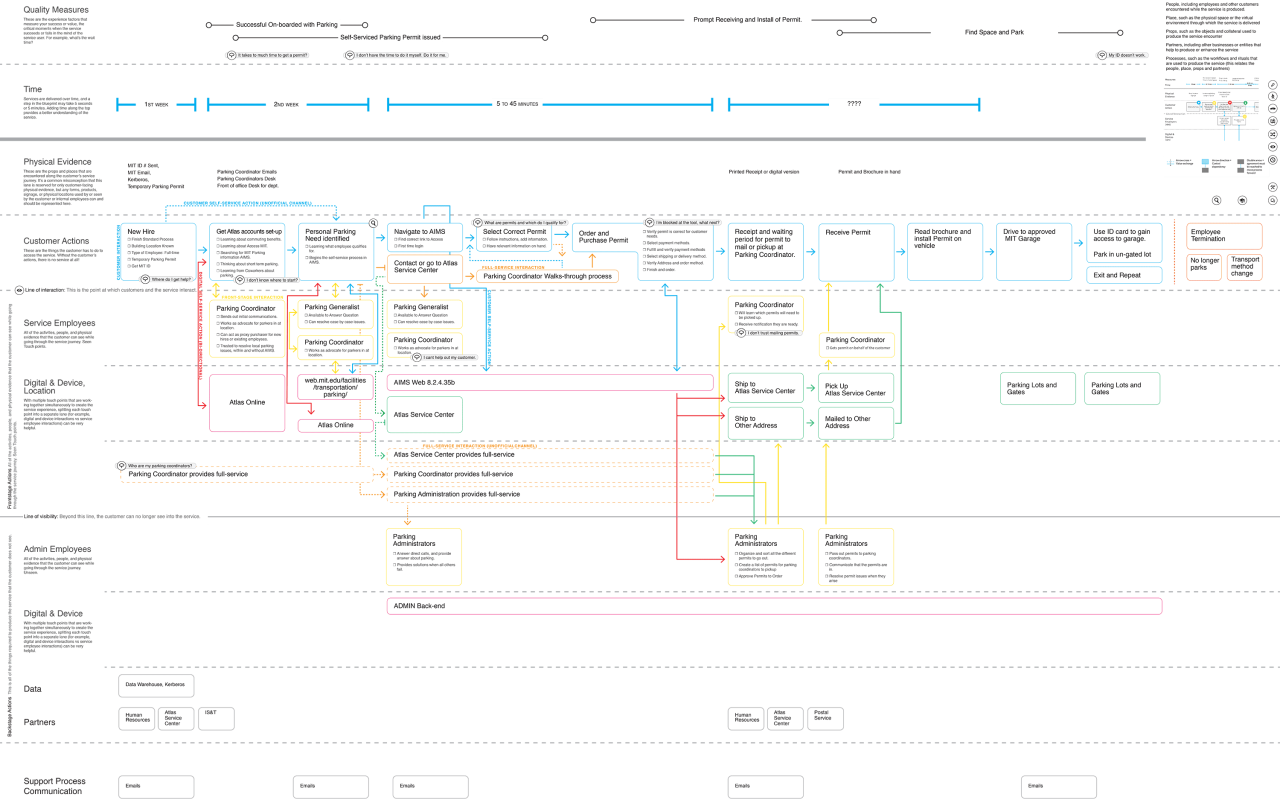

Case Study: MIT GAP Usability Testing and Enhancements

Making the Graduate Appointment Portal a more useful tool by enhancing copy and creation of appointments, making data entry and appointment creation faster, ...

Bring a research philosophy that drives actionable results.

My research philosophy, forged through years of hands-on work, is anchored in driving tangible outcomes. Three core tenets guide my approach:

Strategic, not tactical research. Aligning research goals with user needs and business objectives from the get-go ensures maximum impact. It's about continuously uncovering insights that meaningfully improve users' lives.

Real user engagement is non-negotiable. Personas and assumptions only get us so far. To truly move the needle, we must go to the source - the people whose challenges we aim to solve. Empathy is key.

Research is a team sport. Insights siloed in the research team are insights wasted. Involving cross-functional partners and relentlessly socializing findings democratizes user understanding and hardwires a user-centric mindset into organizational DNA.

Removing personal biases, providing actionable recommendations, and integrating research throughout the development process ensures our work directly improves usability. Thoroughly documenting and sharing research reinforces design decisions and navigates challenges. Prioritizing objective insights to craft user-centric solutions is how I strive to make someone's life a little better.

In the end, research is about improving people's lives. As UX professionals, we have the privilege and responsibility to shape a better world by relentlessly focusing on uncovering and addressing real user needs. This philosophy guides my work and the impact I strive to make daily. The trust users place in us hinges on their belief that we're genuinely looking to make their lives better. That's why they talk to us in the first place.